You can tell a lot about my great-grandfather by what he tells stories about. In his memoir, Gidgiddo tells stories about driving across the continent, back and forth, and buying large quantities of fruit: fifty oranges, or grapefruits, or ten pounds of dates. He tells stories about the wildness of America: encountering snowstorms and hurricanes, or vast swarms of insects, or driving sleepless a day and a night and a day and being only a third of the way home. He tells stories about times he refused to make a profit from a sale, or when mechanics fixed an issue with his car for free. He’s proud to tell stories about spotting a business opportunity, like making a few hundred dollars to start a business in California by cleaning furniture for hotels. He was a man from the old country, but he liked to tell stories about America.

These stories come from a set of tapes he recorded toward the end of his life, which his son my grandfather, also named Louis Lataif, faithfully transcribed the year after he died, shortly after I was born.

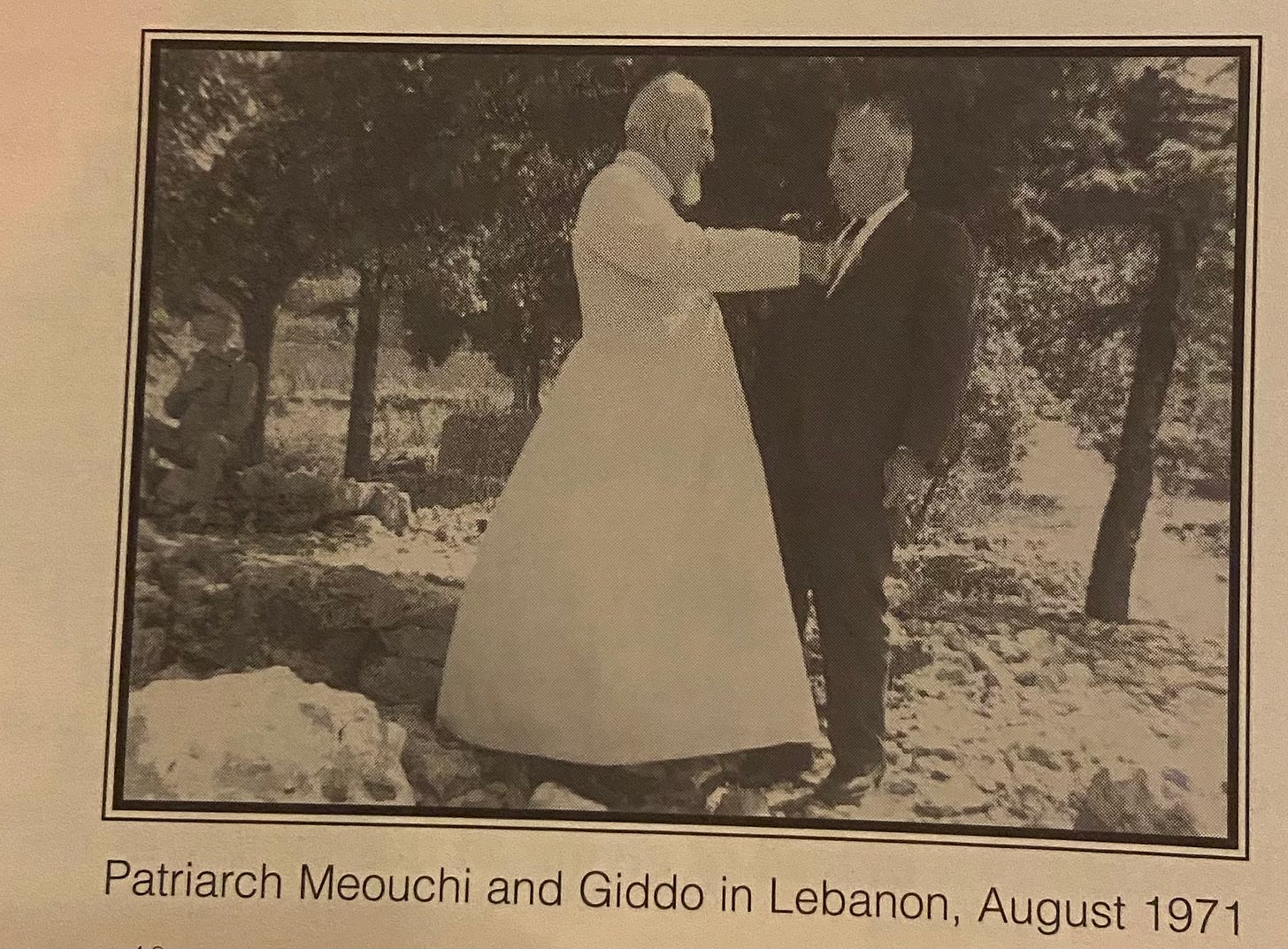

I want to write something a little indulgent, and recount a few of Gidgiddo’s stories. There are more stories than I can tell well here: meetings with Kahlil Gibran and a coronation by the Maronite Patriarch as “King of Arabic Poetry in North America,” his role in founding the Lebanese American Union, a journey to the Chicago World’s Fair, interactions with the Kennedy family, his marriage to his wife within six weeks of meeting her. But here are some.

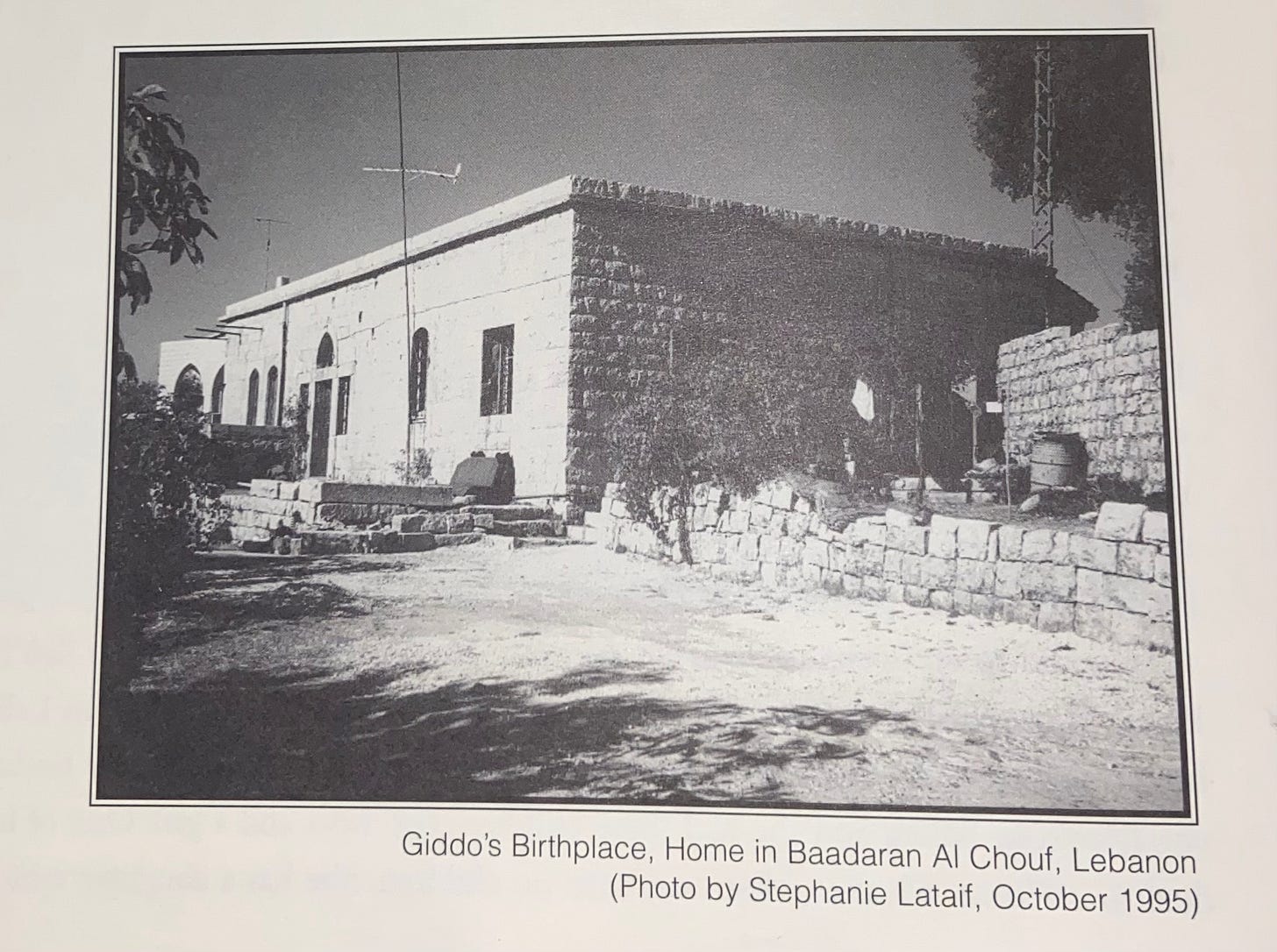

Born Elias Lataif, my great-grandfather spent the first 16 years of his life in the hills north of Beirut, in a town his father and mother were born in. His father was a stonecutter, which is why his family home still looks like this after more than a century.

His journey to the U.S. from the old country mirrors those of millions of early 20th-century immigrants. In 1920, his brother Nasif tells him to come over to Springfield, MA, where he’s working in a motorcycle factory. Elias travels down to the port of Beirut to board a ship that stops in Alexandria, Italy, and finally Marseille, where he celebrates Christmas. There’s another ship crossing the Atlantic from the north coast of France; Elias gets on a train across the country. On the choppy crossing, he’s violently ill, and can’t eat any of the ship’s food: he survives on the present of dried figs and nuts he was bringing for his brother. Here’s his account of arrival:

“In New York we stayed overnight on the ship and the following day they took us from the ship onto Ellis Island. When we saw Ellis Island we knew we were arriving into America. We looked from the boat and we saw the Statue of Liberty; it was a beautiful sight for all the newcomers.

There on Ellis Island, they asked you questions on your entry to this country and they had interpreters for all those who did not speak English. But because I could get along with little English, I had an American interviewer. He asked me why I was coming to America. I told him I was coming here to my brother and that I wanted to go to schools and get my education in America. So immediately he passed me and he put a tag on my lapel and said to me, “You can go on this boat, right to New York City, and there will be a policeman over there to direct you where to go.” I passed in front of everybody, and I came on the boat. When I reached the Bowery of New York, and the first part of Washington Street, I took the tag off. I thought, “geez, I speak English, I don’t have to have a tag, to look like cattle!”

But when I got there I got lost. I didn’t know where to go. It’s a new country. I’ve never seen anything like it: big buildings, tall buildings, lot of noises, lot of ships, taxis. So I asked a policeman, I said, “How can I get to Springfield, Massachusetts?” He looked at my luggage and he found it was all tagged from different parts. He said, “Oh, you’re a newcomer.” I said, “Yes.” He aid, “Where’s your tag?” And I said, “I’ve got it in my pocket.” And he said, “You should not have done that. If you had it on your lapel I would have noticed you and directed you.” So finally he showed me how to go into the subway. And he said, “You take the subway from here, you go to 42nd Street and you get off at the arch of Grand Central Station. And there you ask a policeman when a train is leaving for Springfield, Mass, and he’ll direct you.” And that’s what happened.”

Elias finds his brother in a boarding house with a gaggle of other Lebanese and begins to settle in.

Gidgiddo was a paradigmatic example of a certain form of ethnic assimilation. In America, he happily accepts the name change from Elias to Louis. He’s fiercely proud of his English, deeply capitalist and hungry to make a sale. But he also actively pursues an education in Arabic poetry in New York, befriending local Arab-American newspaper editors and learning from them meter and melody. [This made it much easier for me to dig up historical records: the name Lataif has no right to appear in Brooklyn archives as much as it does.]

Gidgiddo and his children married within Lebanese kinship networks, and live in heavily Lebanese places: Fall River, Brooklyn Heights, later Dearborn, Michigan. In his accounts, there’s no feeling of being trapped between two identities. He’s proud of his Lebanese roots when here, and proud to be an American when visiting Lebanon.

He picks up laboring jobs here and there, but struggles because in his own telling he was “a young fellow, delicate,” and the roles require ruggedness. He goes to work in a men’s hat factory, and things get grisly.

“They cut the rabbit skin and they manufactured from these skins. They call it felt, and they manufacture men’s hats with these little machines that cut the fur, which I never saw in my life before and I didn’t know anything about machinery. They showed me how to put the skin into the roller of the machine and I started to work. Fifteen minutes later, one of these pieces of the skin got caught in the roller and instead of stopping the machine, I picked it with my hand. I didn’t have any finger - I looked around, I didn’t see any finger. So I had to go back home, and go to the doctor. The doctor (they didn’t have much of anesthesia at that time) had to saw the bone with a saw, to make it even, turned the skin around and gave me a couple pills and I went home. And by the night time it was such severe pain - for the whole month - that finger of mine was severely in pain, in pain, continuously in pain. And that was my right hand, and I was a right-handed man. So it made me handicapped now.”

In family lore, the loss of Elias’ finger is now understood as a blessing; indirectly, it leads him off the factory floor and into roles where his salesmanship comes to life. Now locked out of factory work, Elias first learns to cook in a Greek restaurant, then loses his job in the Great Depression. He goes to a factory and finds that he can make a good living buying belts wholesale and selling them for a quarter on the streets of New York. Twists and turns; he ends up in the rug business, where he makes his breakthrough:

“A few months before my first child was going to be born, I went to President Roosevelt’s marvelous home in Hyde Park, New York, and asked his mother if she needed any work to be done. So she gave me a couple of rugs to be repaired, and I repaired them for her, and she liked the work. So I asked her if she would need a rug to buy from me and she said she doesn’t know. But I took one up there and she bought it! That gave me a lot of confidence to go and do some more selling.

So about a month later, after I’d sold her one rug, I found a rug in New York which was quite a large one, and it had some kind of distinguished character to it. It had the design of the seven seas and the seven heavens and the cornerstone of Mecca, and different writings in Arabic were woven into the rug. It looked like a high-class rug. And I knew it’s a size that she could use in her living room. So I picked up the rug from New York and I said I’ll take a chance and show it to Mrs. Roosevelt…

I rang the bell and the butler came in and I said, “I’ve got a very large rug I want to show to her,” and I gave him $5. I said, “Will you help me out: bring it in, and open it up in the hallway?” When she came down, I was standing on the side of the rug, and she looked at the rug and said, “Oh, it looks very good. But I’m going to have Frank see it.”

Frank, of course, is FDR, visiting his momma. Word gets around that Louis Lataif is a friend of the president’s (although Gidgiddo firmly corrects people: he is only “a friend of the Roosevelt family”), and from that moment on is established on more stable footing.

Gidgiddo’s comes to an America full of natural bounty. Here’s his account of crossing the country with his young nephew. There’s so much I love about it, and about the America he encounters.

We took the Southern route over to St. Louis, Missouri. From there we went to Texas - all this land in Texas. We stopped in Dallas. On the highway, all we could see were the telephone poles and rabbits crossing the highway. I was so glad because Paul was with me; he gave me company. And every time we’d stop to eat in a restaurant, there were so many cockroaches, and things were not so clean. It made us very - killed all our appetite.

When we got to Tucson, Arizona, after we passed New Mexico, they said we’d better drive at night, because the desert is very hot. So we had to cross the desert at night. And in the desert, every fifteen or twenty miles, there was a gasoline station. We’d stop, not because we needed gas, but to see if the tires were too full of hot air, or to keep checking on them, to keep them safe. We got to the Death Valley, in the desert, and stopped at this gasoline station and asked them for soda. They gave us soda, and the soda wasn’t cold enough. I sad to the man, you don’t have soda on ice?” He said, “It’s not hot tonight.” I said, “Geez, we feel very warm. How high is the heat?” He said, “It’s only 127 degrees.” I said, “127?!” He said, “Yes, this is the Death Valley - this is a cool night - 127.”

So we kept going. By morning, when the dawn started to show up, we got to the first part of California, into a little town… We stopped into a nice restaurant, they had a good coffee. So I asked the counter man, “Is there any place where I can wash up? He said, “Yeah, go down below the highway. There is hot water and cold water and you can do all your washing.” I thought he was kidding. But I did go down there and I found two streams. Not very big streams, small water, like a fountain: one on the right, one on the left. The left one was lukewarm water coming direct from the mountain, and on the right was cold water. I was amazed because I never knew hot water could come out directly from the mountain. I washed up and I went from there to Los Angeles.”

There’s the oral, almost Biblical rhythms and pacing, and the complete disgust with vermin and uncleanliness of any sort. And there’s the Old World feeling for this new world, of being both a stranger in a strange land and being heartily welcomed into it. The American West is simultaneously a danger for travelers, and a source of marvelous generativity. Water from the rock! A spring in the desert!

Today I live just off Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. Piecing the circumstantial evidence together, it seems likely Louis Lataif lived five blocks away from me, or closer. Probably down Atlantic a couple blocks toward the Lebanese grocery store, Sahadi’s, which his son my grandfather describes as his old haunt.

I tried to avoid sentimentality in writing this, but I do feel sentimental about him, despite never knowing him. Louis Lataif built a remarkably sturdy family legacy, and so much of what constitutes manliness in my family comes from him. My son will be born later this spring. God willing he will meet his own great-grandfather.

Loved this, Santi: an inspiration to better remember my grandparents’ and their parents’ lives.

Not sure that it would feel the same for you as it did me and the wife but you might like “Everything Sad Is Untrue” by Daniel Nayeri. Iranian immigrant family, not Lebanese, but a very interesting way to tell this kind of story. It’s slightly fictionalized. The severed finger story reminded me of a similar-but-different episode in that book.

this is so beautiful! thank you for sharing with us <3