Reviving the Discarded Image

You must conceive yourself looking up at a world lighted, warmed, and resonant with music.

“At his most characteristic, medieval man was not a dreamer nor a wanderer. He was an organizer, a codifier, a builder of systems… Distinction, definition, tabulation were his delight.”

I rarely encounter works of history that manage to place the reader actually within the worldview and outlook of the people being covered. More often than not, a good history makes events evocative, conveying what it was like to be at this battle or at that technological tipping point. But histories struggle to convey the mental and spiritual frameworks of their subjects: it’s easy to describe what (say) an ancient Egyptian believed about the afterlife, much harder to feel it in your body.

So I was almost awestruck at C.S. Lewis’s The Discarded Image, a literary history which manages to put the reader fully inside the mind and experience of the average medieval. I’m going to try and offer a loose sketch of his medieval cosmology here, in the hope that you feel something of its power: how this completely alien way of conceiving of the world actually leads to a different physical experience of being in the world. The mental frameworks of the medievals are so other that stepping into them leads almost to vertigo.

Lewis, a medieval and renaissance literature professor, is of course better known for his Chronicles of Narnia and Christian apologetics. He has a knack for “letting the reader in” in his writing about religion as well. In The Discarded Image, Lewis turns that talent to a different task, of making medieval thought feel urgent and immediately present to a modern audience.

What denizens of the medieval era experienced when they looked out on the world, Lewis argues, is more than anything else a sense of order. To convey this feeling, Lewis focuses on what he calls “the Model,” or the fully fleshed out theology and cosmology they inhabited, and which we’re unaware of. In his words, “I hope to persuade the reader not only that this Model of the Universe is a supreme medieval work of art but that it is in a sense the central work, that in which most particular works were embedded, to which they constantly referred, from which they drew a great deal of their strength.”

Where the Medievals Get Their Ideas

The ordered system of the medieval world was the result of “the overwhelmingly bookish or clerkly character” of medieval culture. If anything, they were a more literary society than we are today. It’s a counterintuitive position, as we’re far more likely to be literate than your given 12-century Briton. But Lewis means literary in a slightly different manner: the written word was accorded far more respect and authority than it is now. He argues that the “single, complex, harmonious mental Model of the Universe” comes from an intense love of system, which in turn comes from a love of what’s been written before.

Medieval man loves old authors, or auctours. “They are bookish. They are indeed very credulous of books. They find it hard to believe that anything an old auctour has said is simply untrue. It was enough for them that they were following good auctours, great clerks, ‘thise olde wise…’ Every writer, if he possibly can, bases himself on an earlier writer, follows an auctour: preferably a Latin one.”

Although the medievals mostly trust the old Mediterranean auctoures, they inherit “a very heterogenous collection of books; Judaic, Pagan, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoical, Primitive Christian, Patristic.” All these sources, and various genres and styles, must be harmonized. There’s “both an urgent need and a glorious opportunity for sorting out and tidying up.” The medieval worldview is a harmonized amalgamation of pieces from a range of cultures.

The Heavens and the Earth

Our folk version of medieval cosmology is completely wrong: their model was more coherent and potent than almost anyone realizes today. For Chalcidius, a late Roman writer who passed Plato down to the medievals, “The geocentric universe is not in the least anthropocentric.” We often get this wrong about the medievals, assuming they thought Earth was central because it’s special. But it’s not, at all. “If we ask why, nevertheless, the Earth is central, Chalcidius has an unexpected answer. It is so placed in order that the celestial dance may have a centre to revolve about - in fact, as an aesthetic convenience for the celestial beings.” Earth is here to be a mechanical pivot point for far greater beings.

The central (and spherical) Earth is surrounded by a series of hollow and transparent globes,” which are called the “spheres,” “heavens,” or occasionally “elements.” Each of these spheres has embedded in it one luminous body: Earth, Luna, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn constitute the seven planets. Outside these spheres you have the stellatum (sphere of the stars) and finally the Primum Mobile, an encasing sphere.

Here’s 12th century theologian Alanus ab Insulis, explaining the universe: In the central castle of the Heavens, “the Emperor sits enthroned. In the lower heavens live the angelic knighthood.” We, on Earth, are “outside the city wall.”

How, we ask, can Heaven be the centre when it is not only on, but outside, the circumference of the whole universe? Lewis: “The spatial order is the opposite of the spiritual, and the material cosmos mirrors, hence reverses, the reality, so that what is truly the rim seems to us the hub.”

The Edge of the Universe

The medievals also have a clear conception of the boundedness of the universe, in a way that’s quite familiar to our modern scientific conceptions. They draw on Aristotle: “Outside the heaven [the last physical edge of the universe] there is neither place nor void nor time. Hence whatever is there is of such a kind as not to occupy space, nor does time affect it.” They clearly understand God as a being outside of time. “Eternity is quite distinct from perpetuity… perpetuity is only the attainment of an endless series of moments, each lost as soon as it is attained. Eternity is the actual and timeless fruition of illimitable life. Time, even endless time, is only an image, almost a parody, of that plenitude; a hopeless attempt to compensate for the transitoriness of its ‘presents’ by infinitely multiplying them.”

The medievals understand cosmic dimensions well, though not perfectly. One document explains that “if a man could travel upwards at the rate of ‘forty mile and yet som del mo’ a day, he would not have reached ‘the highest heaven that ye alday seeth’ in 8000 years.”

A Change in Perspective

Try to place yourself in the geospatial consciousness of your ancestors:

“You must go out on a starry night and walk about half an hour trying to see the sky in terms of the old cosmology. Remember that you now have an absolute Up and Down. The Earth is really the centre, really the lowest place, movement to it from whatever direction is downward movement. As a modern, you located the stars at a great distance. For distance you must now substitute that very special, and far less abstract, sort of distance which we call height; height, which speaks immediately to our muscles and nerves.”

The medieval world was massive but bounded, whereas we conceptualize our universe as infinite. Therefore “our universe is romantic… like looking out over a sea that fades away into mist… and theirs was classical.”

For that reason, “all sense of the pathless, the baffling, and the utterly alien - all agoraphobia - is so markedly absent from medieval poetry.” Pascal’s terror at le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis never enters the mind of Dante.

Also, space isn’t dark. It’s full of light - night and the spatial darkness we see are only because of the earth’s shadow, a conical shaft of darkness in a universe radiated by the Sun. According a Roman poet beloved by the medievals, the spirit as it ascends through the heavens enters a region “compared with which our terrestrial day is only a sort of night.”

And the planets sing: “every planet in his proper sphere in moving makand harmony and sound” (Henryson, Fables). “You must conceive yourself looking up at a world lighted, warmed, and resonant with music.”

Physical “Laws,” and the Law of Love

We instinctively think of the natural world as operating according to “natural laws.” As a result, many medieval concepts seem weirdly anthropomorphic to us. Things “enclyne” (incline) toward each other: “in medieval science the fundamental concept was that of certain sympathies, antipathies, and strivings inherent in matter itself.” The medievals inherit the ancient Greek belief that all objects have an inherent telos or purpose. “Everything has its right place… and if not forcibly restrained, moves thither by a kind of homing instinct.”

Here’s Chaucer in Hous of Fame:

“Every kindly thing that is

Hath a kindly stede ther he

May best in hit conserved be;

Unto which place every thing

Through his kindly enclyning

Moveth for to come to.”

This understanding of physical forces mirrors multiple modern “laws of nature.” So terrestrial objects “kindly stede” to the center of the earth, for “To that centre drawe Desireth every worldes thing” (Gower, Confessio, VII, 234). Chaucer also tells us “The see desyreth naturely to folwen” the Moon (Franklin’s Tale, F 1052), and Bacon that the iron “in particular sympathy moveth to the lodestone,” (Advancement), and so on.

Lewis defends the medieval conception, speaking through an invented medieval interlocutor. “Do you intend your language about laws and obedience any more literally than I intend mine about kindly enclyning? Do you really believe that a falling stone is aware of a directive issued to it by some legislator and feels either a moral or a prudential obligation to conform?” In fact, says Lewis, our language is more anthropomorphic: pigeons do have homing signals, but only humans follow laws.

“But though neither statement can be taken literally, it does not follow that it makes no difference which is used. On the imaginative and emotional level it makes a great difference whether, with the medievals, we project upon the universe our strivings and desires, or with the moderns, our police-system and our traffic regulations. The old language continually suggests a sort of continuity between merely physical events and our most spiritual aspirations. If (in whatever sense) the soul comes from heaven, our appetite for beatitude is itself an instance of ‘kindly enclyning’ for the ‘kindly stede’.”

And in fact, the whole world receives its motive power from “enclyning” to God, who moves “as beloved.” That is, the Primum mobile at the edge of the universe is moved by its love for God, “and, being moved, communicates motion to the rest of the universe.”

This intuition about love as a physical force is completely absent from our culture (except maybe in Interstellar, where it makes a deus ex machina appearance). But it’s the core mechanic of the medieval world.

Worldbuilding in Imagination and Practice

Many of my friends are interested in imagining new worlds. Some see political activism as the path to that world, while others write manifestos, and still others build new tech products. Those with the most transformative visions and deepest frustrations with the current order often say things like “We can’t even imagine a future after capitalism,” or “This technology will be so transformative, we currently can’t even imagine the applications.” Many of these friends appear lit by hidden inner fire, alive to something they feel but can’t quite describe. I don’t have advice for them, or you, but I do find my imaginative capacities expanded in reading The Discarded Image.

Like these contemporary friends, the medievals were builders and active creators. But unlike them, they drew their energy and power from their fleshed out, experiential worldview. By understanding that worldview and actually empathizing with it, even letting ourselves experience it, maybe we can better develop our own.

“The medieval worldview is a harmonized amalgamation of pieces from a range of cultures.” Basically the beginning of scholasticism, right? For me, scholasticism marks the beginning of the end for the early Church phronema. How long is it before the Gospels are on the same level as Amor and Psyche? Along with its sculpture—overtly love-as-eros (erotic!)—seen in every art museum’s neoclassical section? Or Apollo and Daphne? Kinda like Goethe’s eternal feminine? Is Caravaggio’s gritty realism really breathing life into martyrdom, or just satisfying the early modern’s materialistic fascination?

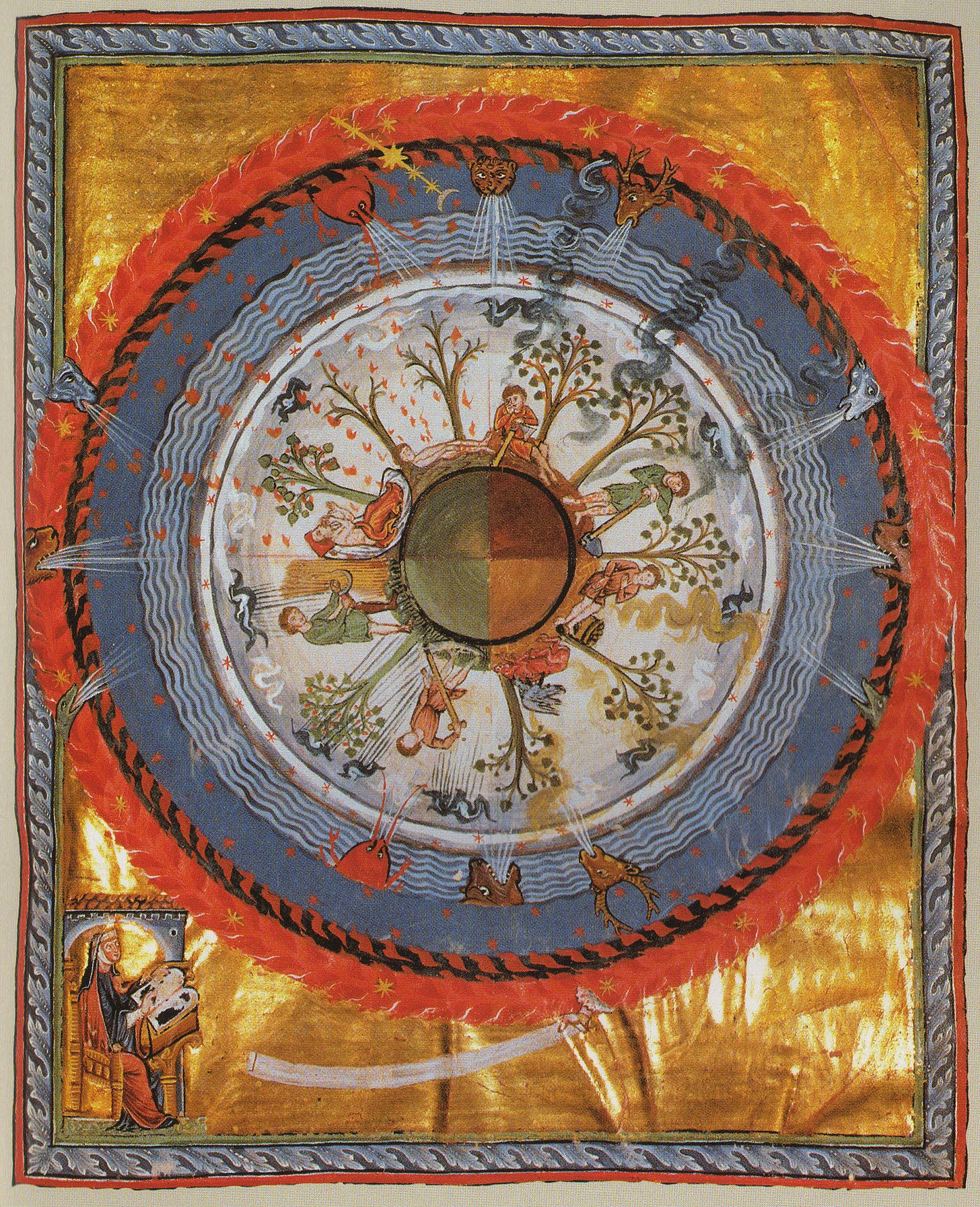

I think the two pics are still swimming in Orthodox imagery though

The second one seems like the apocalyptic eschaton *within* Creation. Like Revelations and Genesis going on at the same time. The middle circle has the first day with Light and Dark divided, surrounded by the firmament. Count the divisions out and the layer corresponding to the 4th day has the sun, moon and stars. From Rev 12 and Phlp. 2:15, interpret the sun as Christ, the moon as Mary (so this is subtle Mary symbolism - that’s why the sun is in the moon’s womb), and the stars as the Church. Obviously the “I am the Light” symbolism sticks out like a sore thumb.

Now it seems like correspondence breaks down here, but four is coincidentally the number of the Earth, and the Earth is not literally the Earth in Genesis, more like “formed Creation.” Count out two more layers and we only have 6 - yikes. The 5th layer is maybe like Rev 13:13? It’s almost like whatever those things are, hailstones or rocks, they’re feeding off the fire and bringing it down to Earth. 5 is also the number of Man, and the day in Genesis that God begins to make creatures. The 6th layer then is the layer of fire. Not a mistake, I think this is a picture of God as a consuming fire, most especially for “the goats on the left.”

Hell as a devouring head is a medieval symbol. All those figures with three heads probably indicate the parody of the trinity (unholy triumvirate) in Revelations—the dragon, the beast from the sea, and the beast from the earth—at different spiritual levels. Notice the one head, the dragon, trying to “devour her child” (Rev 12:4)

More support: since there’s a departure from the Genesis creation poem at layer 4, which contains Christ, we should make note of the psalm for the fourth day of the week (corresponding to the fourth day of Creation - Psalm 93 in the OSB) — “The Lord is the God of vengeance; The God of vengeance declares Himself boldly.” The whole psalm is a plea to separate the wheat from the chaff. The inevitable flip side of the coin of righteousness. Very eschatological in the Light of Christ.

The first image seems a bit simpler. Almost like a snapshot of Genesis 2:15. The sea is like chaos, potential, destruction, which the demons (“powers and principalities”) are sucking Man into on all four corners of the Earth. Pulling formed Creation into the unformed. Hildegard paints herself staring at it.

I haven’t read her stuff, do you know why she was so apocalyptic? Was she a chiliast?

Really soulful, interesting post. I just sent The Discarded Image to my Kindle. And can only wonder what C.S. Lewis would think about the way we think about and use "The Cloud."