When people ride for technocapital, their motivations are usually clear. Nick Land, who coined the term, is a misanthrope. He doesn’t like humans much, so the idea that there could be an entity coming, already being born, drawing itself into existence by hyperstitionally preying on the dreams of humanity, cannibalizing their desires, wearing “the invisible hand” as an ideological skin: he’s into that. “Techno-economic interactivity crumbles social order in auto-sophisticating machine runaway,” as he would put it, and that’s good. You’re being colonized by an entity that doesn’t care about you, except insofar as you make a good host.

There are other technocapital advocates. Nyx Land inherits the original Land’s misanthropy and adds gender dysphoria. Technocapital is good because, in the long run, it turns boys into women, in the same way that industrial chemicals turn the frogs gay and warmer oceans make turtles female. Read the blackpaper. “The liberation of the female sex by acceleration in general, towards maximizing productive potential under such a time that the male is no longer needed.” There’s no place in the hyperstitional future for individual action, protection of the household, physical labor, or other typically male traits: the inhuman will reproduce itself, the human will die away, and good riddance.

These boosters of techno-capital like it because it’s an end in itself, which lets them avoid asking questions about the ends of man himself. Which is why it’s odd to see the same ideas used for ostensibly pro-human political projects. Marc Andreessen cites the first Land, approvingly, in his new Techno-Optimist Manifesto.

“Combine technology and markets and you get what Nick Land has termed the technocapital machine, the engine of perpetual material creation, growth, and abundance.”

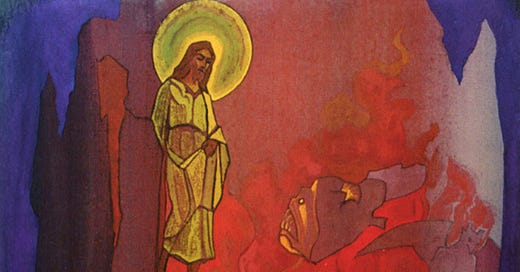

Andreessen is consciously bastardizing Land here, because what he terms “perpetual creation growth and abundance,” Land understands as a roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour.

Andreessen, a Straussian, likes to do this with his sources. The first quote of the essay is from Walker Percy, who sees individuals trapped within technological society. Andreessen uses him to make the argument that only technological society can free us from the things that entrap us. It’s a neat inversion, but it doesn’t work.

Thinkers like Percy, or Heidegger, or Land, or Byung-Chul Han, think we’re shaped by technocapital (or by modernity, if you like). They suggest, and this is obvious to anyone who is reading this on social media, that technologies make us different kinds of people. This isn’t always bad, but it’s always the case, they say: I’m not the same person as I was before I used the phone, or the food delivery service, or the chatbot. And according to Heidegger, this changing process is always happening even if I’m not using the specific piece of technology. I could cut lumber with the same ax as my grandfather did, but if I now supply that lumber to the industrial mill, I am “standing reserve” for that mechanical process. By seeing technologically, I risk losing a part of myself.

Andreessen isn’t interested in this dynamic, not on the surface of the text. Instead, “human wants and needs are infinite,” and technology is simply the vector for the fulfillment of those needs. Those needs generate more market demand, which generates more innovation, which generates more wants and needs, and the machine rolls on.

Once I sat with my friends and listened to a well known biotechnologist speak about defeating death. This technologist spoke about their mom growing older, and how impossibly painful it was to watch, and how, if all things worked out, the doctors would soon be able to remove her mother’s head just before death, freeze it, slice the brain up into wafer-thin pieces, and reconstruct her consciousness in a vat. (More on this in another essay.)

I think about my mom getting older too, although my hope is in the life of the world to come and not in a surgeon removing her head. But that vision of technology, as weird and eldritch and sinister as it may be, is more human than the Landian/Andreessenian vision. The L/A view is of the glory of the runaway machine, its size and our tiny scale.

Andreessen dismisses my view as so much sentimental nonsense: “Love doesn’t scale.” This evening, I talked to my son, who didn’t exist in any form a year and a half ago, and who now stares at me adoringly and uncomprehendingly while I try and point out the zucchini on the right of his tray table and the banana on his left. He just gazes at me and smiles and then slowly giggles as I talk. And he’s a 150% return on familial investment, with almost limitless potential for further personal and genetic line growth.

By contrast, when Andreessen lauds people and the human, it’s for their ability to be plugged into the technocapital machine. “People are the ultimate resource – with more people come more creativity, more new ideas, and more technological progress.”

There is a dangerous contradiction that he avoids, though: “We believe material abundance therefore ultimately means more people – a lot more people – which in turn leads to more abundance.” But this is the opposite dynamic to what we’ve seen play out in every country in the world, that birth rates decline as material abundance increases. Perhaps the artificial womb beckons.

To be clear, I’m in Andreessen’s camp in more ways than one, I like technological progress, and I work for an institution dedicated to it. Silicon Valley techno-optimism is an improvement over many ideological projects. But I’m a techno-optimist because I think the only way out is through, and that technology must be made to serve human ends. Without a better philosophy of what a human is for, and a higher view of humans than of the technocapital machine, it’s just a vehicle for Land’s creatures from beyond the void.

I’ve been off schedule for the past two months. I’ll be trying to publish something, anything, twice a month going forward. Holler if I don’t.

I came across this piece while Googling a definition of technocapital and then began reading your other work. It is all quite interesting and I will be recommending it, especially Statecraft, to some friends. I realize this might be a tall order, but can you recommend a primer or two on Land's philosophy that's accessible to a layman? (As what counts as a "layman" is terribly vague, maybe "educated and able to use technology" is as good a start as any.) For some context, I'm working through a particular set of questions around technology use and the Internet with reference to the value neutral thesis, especially as it relates to the structures of social media.

Mostly unrelated, but since I don't know how else to reach you: you asked a question some months ago on X about why small groups are something like the dominant social expression of American (or Evangelical) Christianity. The phenomenon seems to have arisen in response to economic changes during the industrial revolution, and (later) the effects of the automobile. As you know, the home/village and local parish used to be the center of economic and social life and the primary locus of identity formation. As life shifted to factories and cities and everything became much more mobile, the organic life that church discipleship / apprenticeship was built around evaporated. Christians responded to these trends with new (mediating?) institutions like discipleship groups or societies that often met midweek, and thus modern small groups were born. Mark Sayers (an Australian pastor and author) recently discussed this on the Rebuilders podcast, arguing this is possibly an outdated model given shifts in the information age: https://youtu.be/IJ8vwpRdH_c?t=1587 and Alastair Roberts (an independent Anglican scholar) also addressed the rise and function of small groups (in his typically insightful manner) in a Q&A a few years ago: https://youtu.be/Hx7fc-ChiVs?feature=shared

It is fascinating to view modern theological controversies, most of which were questions which ancient and medieval Christians generally considered settled, as arising almost entirely from the disorientating effect of modern technology on our social arrangements and material conditions. It's possible to overfit--if that's the right term--this framework, but it has helped me understand why these debates arise and why they seem to be so interminable. Is all ecclesiology downstream of technology?

Interesting and thoughtful, thank you.

It's a nuanced topic.