by Ernst Jünger, translated from the German by Tess Lewis, introduction by Jessi Jezewska Stevens, afterword by Maurice Blanchot

NYRB, 144 pp, $10.47

I haven’t quite found the words yet, but this will be one of my favorite books of the year. It’s a dream of an allegory, something like Lewis’s Till We Have Faces, with that same kind of radiant truer-than-true brilliance.

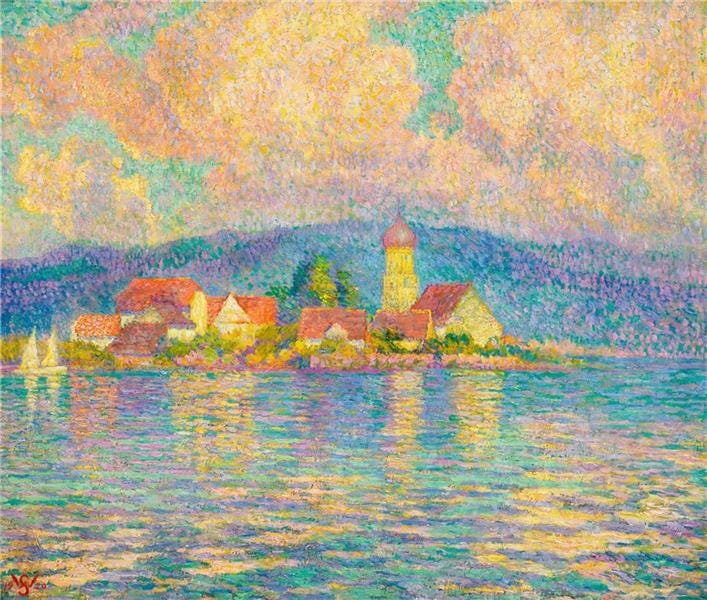

Translator Tess Lewis, in another essay, taught me the German word Wortschatz, or word-hoard. Marble Cliffs is back in vogue owing to her new translation of the Jünger novella, which comes across at once as deeply Germanic, with its wortschatz of recurring compounds (“wisemen,” “lanceheads,” “spellbound”), and as Ancient Greek, although perhaps the latter is the result of the setting: sheer marble cliffs overlooking a Mediterranean lake, ringed by vineyards and a little monastery.

Jünger’s unnamed Mary Sue is a botanist with a Linnaean fixation, trusting that words, wielded correctly, order the world. I won’t spoil the fantasy, except to say that not much happens, and that which does happen is telegraphed from the very first page. But it’s all conveyed with astonishing, piercing intensity and a narrative stillness that doesn’t waver even in the kinetic final scene.

Originally published in 1939, Jünger’s anti-Nazi allegory was the only regime-critical book allowed to reach print, and reached then-viral reach before getting kiboshed in 1942 by the Gestapo. In an afterword, Jünger describes how popular the book became on the front lines and in occupied Paris, where he spent the war as a kind of military dilettante.

According to Bruce Chatwin, “How it slipped through the censor machine of Dr. Goebbels is less of a mystery when one realizes that Braquemart [a minor character] was modeled on Dr. Goebbels himself, who was flattered and amused by it, and later alarmed by its popularity among the officer caste.”

Jünger was a strange bird: vigorously anti-Nazi, but from the right; all cold clarity in the heat of battle, but a true aesthete who later wrote extensively about his experiences with psychedelics; a staunch German nationalist who found himself overcome with self-revulsion on seeing Jewish girls wearing the yellow star.

Young Lords and Their Traces

Theaster Gates

Exhibition, The New Museum

Jünger, for all his activity, was an archivist, committed to saving things from destruction. Chatwin: “Indeed, he had saved a lot of things in the blitzkrieg. A week earlier, he had saved the Cathedral of Laon from looters. He had saved the city’s library with its manuscripts of the Carolingian kings. And he had employed an out-of-work wine waiter to inspect some private cellars and save some good bottles for himself.”

Like Jünger, Chicago South Side artist Theaster Gates specializes in salvaging precious items, and seems to exert a magnetic pull on them. His lapidary survey exhibition at the New Museum just closed, but here’s a good video tour. It was full of stuff: a Russian scholar’s 20,000 book strong library, African tribal sculptures, a Hammond B3, hairpins and doodads from black cultural figures. There’s an interesting tension in Gates’ work: he professes a black radicalism, but his process is deeply conservative, focused as it is on memory and physical artifacts.

I’ve read two especially provocative essays recently on global development.

“But instead of proffering the American Revolution as a model for the emerging nations of the decolonizing world, American policy-makers in the 1950s and ’60s rolled out a more all-encompassing program: modernization theory. This was the self-flattering story that explained the labor of decolonization and global capitalist integration as a manageable and inevitable process: the entry of new nations into modernity itself. The theory was consecrated in Walt Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1960), an inverted Leninist tract that neatly substituted a liberal end point for history in place of a communist one. By 1968, the leading historian of American liberalism, Louis Hartz, appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and explained that the Third World revolutions were more akin to the birth pangs of Europe leaving the Middle Ages than either the French or American Revolution.”

The thesis: the vast majority of successful globalization has occurred in China (and to a lesser extent the rest of East Asia), while much of the third world has not progressed much at all, or minimally without moving substantial chunks of its population from poverty into lower-middle class status. The East Asian success story has left these countries no room for a transition to manufacturing, but deagrarianization has already occurred, leaving them trapped in a service-based, informal economy system in which masses of underemployed young men create political instability.

Here’s the first page and a half of On The Marble Cliffs:

You all know the fierce melancholy that overcomes us at the memory of happy times. How irrevocably these have fled, and we find ourselves separated from them by something even more pitiless than vast distances. In the afterglow, too, these images appear even more enticing; we think of them as we do of a dead lover's body, buried deep in the ground, now appearing before us like a mirage, and we tremble at its greater, more spiritual splendor. Again and again, in our parched dreams we grope for every detail, every lineament of the past. And we feel we have not been allotted our full share of life and love, yet no amount of regret can bring back what we have lost. Oh, if only this emotion could serve as a lesson for every moment of happiness we do enjoy!

And the memory of our years under sun and moon become sweeter still when fear has put an abrupt end to them. Only then do we recognize how fortunate we humans are to live from day to day in our small communities, under peaceful roofs, engaged in pleasant conversation, and with affectionate greetings morning and night. Alas, we always recognize too late that these simple things offered us a cornucopia of riches.

So it is that I, too, look back on the years we lived on the Grand Marina- only in memory are their charms revealed. To be sure, at the time it seemed that many a problem and care clouded our days and above all that we needed be on guard against the Head Forester. That is why we lived with a certain austerity and dressed simply even though bound by no vow. Twice a year, however, we let our garments' rich red lining show--once in spring and once in autumn.